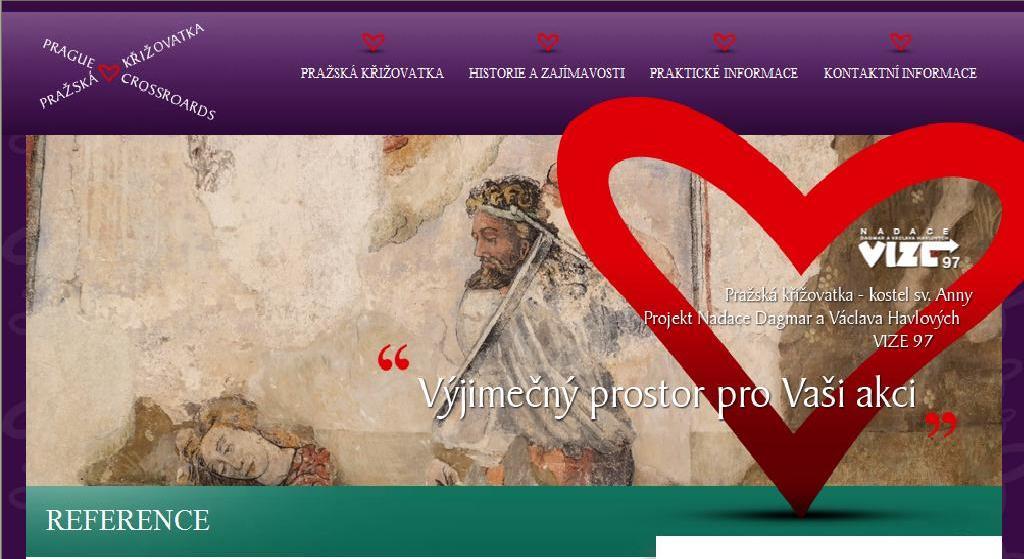

Extensive fragments of outstanding wall paintings have been preserved in the chancel of the former church of St Lawrence of St Anne’s convent. The most important of them were created some time around 1375, towards the end of the reign of the Emperor Charles IV, at a time when the lands of the Bohemian Crown were at a high point of their cultural history. At that time the walls of the recently reconstructed chancel were covered by three monumental scenes in the style of Master Theodoricus, or a group of painters working under his leadership during the previous decades on the decoration of the Chapel of the Holy Rood at Karlštejn, immediately preceding the work of another outstanding figure in the world history of art, the anonymous master, known after his best-known surviving creation the Master of the Třeboň Altar. It is highly probable that that painter, who employed the technique of chiaroscuro a hundred years earlier than Leonardo da Vinci, worked with Theodoricus’ workshop at Karlštejn, and a number of analogies suggest he was also one of the painters of the St Anne’s church frescoes.

Almost the entire free space of the south wall of the chancel, measuring 8 x 9 metres, is taken up with a scene of a Lamentation of Christ, in the centre of which is still preserved a central group of the seated Virgin Mary with the horizontally composed figure of Christ on her lap. Christ’s head is supported by St John kneeling, behind whom we can make out another female figure (now without a head unfortunately) in a yellow robe. Beneath the central group, Joseph of Arimathea is preparing the tomb and the shroud. The massive horizontally-composed tomb has been interestingly overpainted by the artist in the left corner – the shorter side, with the perspective running originally running “correctly” rightwards to the rear, was subsequently painted over to give the entire tomb the opposite perspective and its side walls now open wide to the rear. This is undoubtedly a question of “second thoughts” on the part of the artist, which perhaps (in the spirit of the then tradition of “inverse perspective” that is still alive in iconography) was intended to emphasise the transcendental, spiritual, unearthly significance of the entire event by means of the deliberately irrational unreality of the space. On the left, a procession of foot soldiers and cavalrymen are leaving Calvary after attending the crucifixion. To the right of the tomb, in a corner of the preserved painting there is a fragment of one of the implements of torture – a ladder spattered with Christ’s blood; there is a tree next to the tomb and near it the fragments of the head of a figure on a much smaller scale. The scene is set into a chiaroscuro-painted landscape with development of depth, and with characteristic details of clumps of grass and white flowers. In the background can be seen the remnants of an acanthus decoration. The bottom edge of the scene is bordered by a massive painted frame with a band of quatrefoils. At the very end of the chancel can be found the separate figure of St Eustache.

On the opposite wall of the chancel is a painting of the Seven Sacraments, an almost square composition with the original format of cca. 5 x 4.5 m. In the centre is a monumental three-metre-high figure of Christ on the cross, the central symbol of the holiest of the sacraments – the Eucharist. Beneath the foot of the cross a Eucharistic chalice stands on an altar and into it flows a mighty stream of blood from Christ’s wounds. Before the altar a priest raises the host, also soaked in Christ’s blood. The other sacraments are depicted by what are essentially genre illustrations on a smaller scale, arranged in two symmetrical groups of three on either side of the crucified Christ. The second most important sacrament – baptism – is illustrated in the centre of the left field. At top left a wedding procession and a fragment of the figure of a bride represent the sacrament of marriage and below left is shown the sacrament of confirmation, proved with certainty by a fragment of the Latin inscription [con]firmacio. The fragment of the upper right field shows the sacrament of holy orders, while the other two are totally destroyed and originally bore paintings of the sacrament of penance and reconciliation and the sacrament of extreme unction. The bottom edge consists of a miniature paintings of purgatory from which a delightful angel with blue wings is releasing one of the souls who has received grace, characterised once more by the stream of Christ’s blood flowing onto it.

To the right of the Seven Sacraments is one of the most popular subjects of that period The Adoration of the Magi, three large separate fragments of which have survived. At the left is seated the Virgin Mary in a blue cloak holding the infant Jesus on her lap. Behind her one can make out the wattle wall and roof of the stable of Bethlehem. The gaze of the Mary and Jesus is fixed on the first kneeling king, of whom only the outline of his back has survived. Almost nothing has survived of the second king either. The best preserved is the figure of the third king in a green raiment, holding a bowl in his right hand and the handle of a walking stick in his left. In the background is a freely painted depiction of rock formations, details of vegetation and a beautiful motif of three horses going behind one of the cliffs. Of particular interest is the fact that the face of the third king is very similar to contemporary portraits of Charles IV’s son Wenceslas IV. In view of the fact that the theme of the three magi was often used for crypto-portraits of monarchs and the convent of St Anne was a royal foundation – confirmed by King John of Luxemburg, the Emperor Charles IV and Wenceslas IV, one may assume that the faces of the three magi were those of all three monarchs of the Luxemburg dynasty.

The paintings described were by no means the only wall decorations in the church in the course of history. Very soon afterwards the lower part of the south wall received a painting of St Barbara that partly encroached on the frame and landscape of the Lamentation of Christ. The figure of the saint is still quite visible, with her typical attribute of a cup and the strikingly red architecture of the interior of the tower in which she was imprisoned. The paintings of the bottom part of the northern wall date to the years around the turn of the 15th century – a fragment of the enthroned Madonna with the Infant Jesus and St John and St Jerome, (the latter with unusually youthful features, in contrast to the usual elderly portrayal of this pilgrim to Bethlehem and biblical translator, such as in the unfinished painting by Leonardo) and a beautiful detail illustrating the legend of his removing the thorn from the paw of the lion, which later became Jerome’s fellow pilgrim and attribute. Alongside the portal into the neighbouring convent, is a painting of the Consecratio virginis (the admission of a novice into the order of nuns when the bishop, as Christ’s representative confirms the mystical marriage with a gold ring, observed excitedly by secular and saintly figures). Of the other paintings, mention should be made of a beautiful isolated fragment of a royal procession.

The Hussite Wars drastically ruptured the continuity of cultural development in the Czech lands. At a time when Brunelleschi was building the dome of the Florence cathedral, churches in Bohemia were being plundered and artistic activity almost came to a halt. Even long after the Battle of Lipan, which marked the end of the wars, there were hardly any works to be found that were comparable with the previous period. All the more surprising therefore is the painting that continues to grab one’s attention: The Assumption of the Virgin with the Apostles Philip and James in the lower part of the southern wall. It is qualitatively quite unique in the context of the period because it is still inspired by the pre-Hussite tradition of Třeboň Altar, and links it with contemporary trends of West European late Gothic. Judging by the figure of the donor with a coat of arms displaying an arrow whose base is divided and curved, it was commissioned some time in the 1470s by Jaroslav of Dubá, assessor at the chamber court.

Gothic painting dominated the interior of the church until the repairs carried out in the 1620s, when they were covered over and replaced by new Renaissance-style decoration. But neither they, nor the subsequent paintings executed during the Baroque period before the convent was closed for good by Joseph II in 1782, came anywhere near the standard of their Gothic predecessors.

(Text and photographs by Martin Pavala, of the TRADICE, s.r.o. firm of restorers)

The process of fresco restoration

The Assumption of the Virgin

St Eustache

The Adoration of the Magi

The Lamentation of Christ

Fragments of Gothick and Renaissances paitings of the north wall

The Seven Sacraments

Extensive fragments of outstanding wall paintings have been preserved in the chancel of the former church of St Lawrence of St Anne’s convent. The most important of them were created some time around 1375, towards the end of the reign of the Emperor Charles IV, at a time when the lands of the Bohemian Crown were at a high point of their cultural history. At that time the walls of the recently reconstructed chancel were covered by three monumental scenes in the style of Master Theodoricus, or a group of painters working under his leadership during the previous decades on the decoration of the Chapel of the Holy Rood at Karlštejn, immediately preceding the work of another outstanding figure in the world history of art, the anonymous master, known after his best-known surviving creation the Master of the Třeboň Altar. It is highly probable that that painter, who employed the technique of chiaroscuro a hundred years earlier than Leonardo da Vinci, worked with Theodoricus’ workshop at Karlštejn, and a number of analogies suggest he was also one of the painters of the St Anne’s church frescoes.

Almost the entire free space of the south wall of the chancel, measuring 8 x 9 metres, is taken up with a scene of a Lamentation of Christ, in the centre of which is still preserved a central group of the seated Virgin Mary with the horizontally composed figure of Christ on her lap. Christ’s head is supported by St John kneeling, behind whom we can make out another female figure (now without a head unfortunately) in a yellow robe. Beneath the central group, Joseph of Arimathea is preparing the tomb and the shroud. The massive horizontally-composed tomb has been interestingly overpainted by the artist in the left corner – the shorter side, with the perspective running originally running “correctly” rightwards to the rear, was subsequently painted over to give the entire tomb the opposite perspective and its side walls now open wide to the rear. This is undoubtedly a question of “second thoughts” on the part of the artist, which perhaps (in the spirit of the then tradition of “inverse perspective” that is still alive in iconography) was intended to emphasise the transcendental, spiritual, unearthly significance of the entire event by means of the deliberately irrational unreality of the space. On the left, a procession of foot soldiers and cavalrymen are leaving Calvary after attending the crucifixion. To the right of the tomb, in a corner of the preserved painting there is a fragment of one of the implements of torture – a ladder spattered with Christ’s blood; there is a tree next to the tomb and near it the fragments of the head of a figure on a much smaller scale. The scene is set into a chiaroscuro-painted landscape with development of depth, and with characteristic details of clumps of grass and white flowers. In the background can be seen the remnants of an acanthus decoration. The bottom edge of the scene is bordered by a massive painted frame with a band of quatrefoils. At the very end of the chancel can be found the separate figure of St Eustache.

On the opposite wall of the chancel is a painting of the Seven Sacraments, an almost square composition with the original format of cca. 5 x 4.5 m. In the centre is a monumental three-metre-high figure of Christ on the cross, the central symbol of the holiest of the sacraments – the Eucharist. Beneath the foot of the cross a Eucharistic chalice stands on an altar and into it flows a mighty stream of blood from Christ’s wounds. Before the altar a priest raises the host, also soaked in Christ’s blood. The other sacraments are depicted by what are essentially genre illustrations on a smaller scale, arranged in two symmetrical groups of three on either side of the crucified Christ. The second most important sacrament – baptism – is illustrated in the centre of the left field. At top left a wedding procession and a fragment of the figure of a bride represent the sacrament of marriage and below left is shown the sacrament of confirmation, proved with certainty by a fragment of the Latin inscription [con]firmacio. The fragment of the upper right field shows the sacrament of holy orders, while the other two are totally destroyed and originally bore paintings of the sacrament of penance and reconciliation and the sacrament of extreme unction. The bottom edge consists of a miniature paintings of purgatory from which a delightful angel with blue wings is releasing one of the souls who has received grace, characterised once more by the stream of Christ’s blood flowing onto it.

To the right of the Seven Sacraments is one of the most popular subjects of that period The Adoration of the Magi, three large separate fragments of which have survived. At the left is seated the Virgin Mary in a blue cloak holding the infant Jesus on her lap. Behind her one can make out the wattle wall and roof of the stable of Bethlehem. The gaze of the Mary and Jesus is fixed on the first kneeling king, of whom only the outline of his back has survived. Almost nothing has survived of the second king either. The best preserved is the figure of the third king in a green raiment, holding a bowl in his right hand and the handle of a walking stick in his left. In the background is a freely painted depiction of rock formations, details of vegetation and a beautiful motif of three horses going behind one of the cliffs. Of particular interest is the fact that the face of the third king is very similar to contemporary portraits of Charles IV’s son Wenceslas IV. In view of the fact that the theme of the three magi was often used for crypto-portraits of monarchs and the convent of St Anne was a royal foundation – confirmed by King John of Luxemburg, the Emperor Charles IV and Wenceslas IV, one may assume that the faces of the three magi were those of all three monarchs of the Luxemburg dynasty.

The paintings described were by no means the only wall decorations in the church in the course of history. Very soon afterwards the lower part of the south wall received a painting of St Barbara that partly encroached on the frame and landscape of the Lamentation of Christ. The figure of the saint is still quite visible, with her typical attribute of a cup and the strikingly red architecture of the interior of the tower in which she was imprisoned. The paintings of the bottom part of the northern wall date to the years around the turn of the 15th century – a fragment of the enthroned Madonna with the Infant Jesus and St John and St Jerome, (the latter with unusually youthful features, in contrast to the usual elderly portrayal of this pilgrim to Bethlehem and biblical translator, such as in the unfinished painting by Leonardo) and a beautiful detail illustrating the legend of his removing the thorn from the paw of the lion, which later became Jerome’s fellow pilgrim and attribute. Alongside the portal into the neighbouring convent, is a painting of the Consecratio virginis (the admission of a novice into the order of nuns when the bishop, as Christ’s representative confirms the mystical marriage with a gold ring, observed excitedly by secular and saintly figures). Of the other paintings, mention should be made of a beautiful isolated fragment of a royal procession.

The Hussite Wars drastically ruptured the continuity of cultural development in the Czech lands. At a time when Brunelleschi was building the dome of the Florence cathedral, churches in Bohemia were being plundered and artistic activity almost came to a halt. Even long after the Battle of Lipan, which marked the end of the wars, there were hardly any works to be found that were comparable with the previous period. All the more surprising therefore is the painting that continues to grab one’s attention: The Assumption of the Virgin with the Apostles Philip and James in the lower part of the southern wall. It is qualitatively quite unique in the context of the period because it is still inspired by the pre-Hussite tradition of Třeboň Altar, and links it with contemporary trends of West European late Gothic. Judging by the figure of the donor with a coat of arms displaying an arrow whose base is divided and curved, it was commissioned some time in the 1470s by Jaroslav of Dubá, assessor at the chamber court.

Gothic painting dominated the interior of the church until the repairs carried out in the 1620s, when they were covered over and replaced by new Renaissance-style decoration. But neither they, nor the subsequent paintings executed during the Baroque period before the convent was closed for good by Joseph II in 1782, came anywhere near the standard of their Gothic predecessors.

(Text and photographs by Martin Pavala, of the TRADICE, s.r.o. firm of restorers)